What Is an Attack Vector?

An attack vector is the path or method a malicious actor uses to gain unauthorized access to a computer, system, or network. It exploits a vulnerability in the ‘attack surface’, which includes all potential entry points like software flaws, human error, or weak credentials. Common attack vectors include phishing, malware, unpatched software, weak passwords, and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks.

Types of attack vectors include:

- Malware: Malicious software such as viruses, worms, and ransomware that can compromise systems to steal data, cause damage, or gain control.

- Phishing: A form of social engineering where attackers trick users into revealing sensitive information, such as login credentials, through deceptive emails or websites.

- Weak or compromised credentials: Using weak passwords or stolen login information to gain access to accounts and systems. This is one of the most common attack vectors.

- Unpatched systems: Exploiting vulnerabilities in software that has not been updated or patched.

- SQL injection: A web-based attack that involves inserting malicious SQL code into database queries to manipulate a web application.

- Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS): Overwhelming a system with a flood of traffic to make it unavailable to legitimate users.

- Insider threats: Malicious actions taken by someone with legitimate access to a system, such as an employee.

Man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks: Intercepting communication between two parties to eavesdrop or alter the data being exchanged.

Attack Vector vs. Attack Surface

While an attack vector refers to the specific method or pathway an attacker uses to gain unauthorized access, the attack surface is the total set of points where an attacker could try to enter or extract data from a system. In other words, attack vectors are the individual tools or tactics, while the attack surface encompasses all possible entry points.

For example, phishing emails, unsecured APIs, and outdated software are all attack vectors. The attack surface, however, includes every component that could be exploited: User interfaces, network ports, software dependencies, and even user behavior. The larger the attack surface, the more opportunities exist for attackers to find a way in.

Minimizing the attack surface is a key defensive strategy. It involves reducing the number of potential vectors by disabling unused services, applying security patches, enforcing strong authentication, and limiting user privileges.

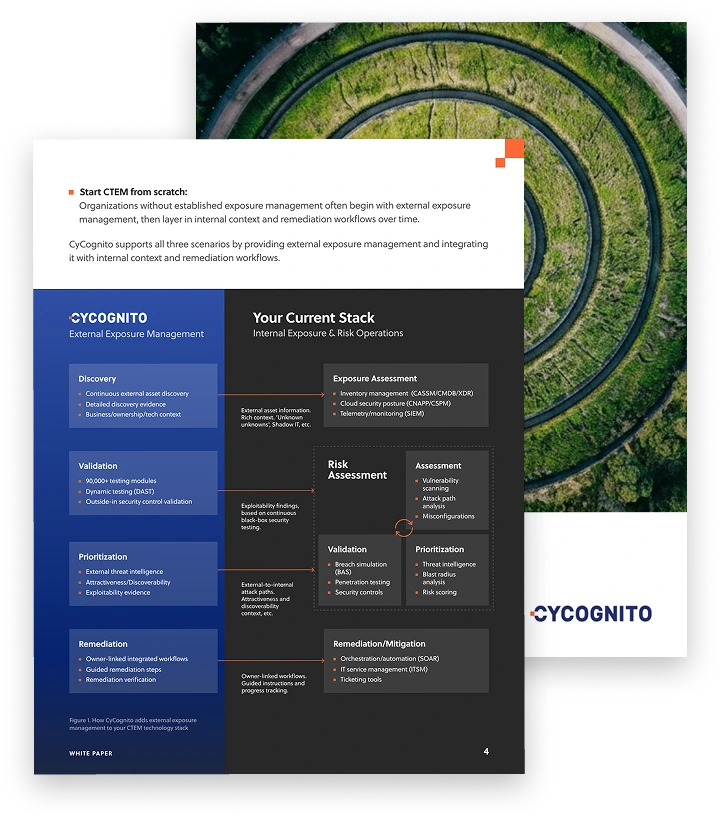

Operationalizing CTEM Through External Exposure Management

CTEM breaks when it turns into vulnerability chasing. Too many issues, weak proof, and constant escalation…

This whitepaper offers a practical starting point for operationalizing CTEM, covering what to measure, where to start, and what “good” looks like across the core steps.

Passive vs. Active Attack Vectors

Attack vectors can be categorized as passive or active based on the attacker’s level of interaction with the target system.

Passive attack vectors involve monitoring or intercepting data without altering system resources or actively engaging the target. Examples include eavesdropping on unencrypted network traffic or analyzing metadata. These attacks aim to gather intelligence without detection and often serve as reconnaissance for future active attacks.

Active attack vectors involve direct interaction with the target to alter, disrupt, or damage systems and data. These include actions like injecting malware, exploiting software vulnerabilities, or launching denial-of-service attacks. Active attacks are more likely to be detected due to their disruptive nature.

Attack Vector vs. Attack Path

While an attack vector is the method or technique used to initiate a cyberattack, an attack path refers to the sequence of steps or chain of exploits an attacker follows to reach their objective within a system.

An attack path often involves multiple stages, starting with an initial entry via a specific vector (such as a phishing email or exposed port) and progressing through lateral movements, privilege escalations, or further exploitation until the attacker achieves their goal, like data exfiltration or system takeover.

In short, the attack vector is how the attacker gets in, while the attack path is what they do next once inside. Mapping potential attack paths allows defenders to identify high-risk combinations of vulnerabilities and misconfigurations that could be exploited in sequence, even if individual flaws seem low-risk on their own.

Common Types and Examples of Attack Vectors

Malware, Trojan, and Ransomware Injections

These attacks begin when users unknowingly download malicious software that disguises itself as legitimate. Trojans may open backdoors, steal data, or facilitate further malware infections. General-purpose malware can perform a wide range of actions, from spying on users to turning machines into botnet nodes. Ransomware encrypts files or systems, then demands payment for decryption keys. These attacks can halt business operations and result in data loss, even after payment.

Common attack vectors:

- Email attachments containing disguised executable files

- Drive-by downloads from compromised or malicious websites

- Infected software installers from third-party sources

- Malvertising delivering malware through ad networks

- USB drives with preloaded malware

- Exploits in document files (e.g., Word macros)

- Fake software updates prompting users to install malware

- Remote desktop protocol (RDP) abuse for direct malware delivery

Phishing and Social Engineering

Phishing is a highly prevalent attack vector due to its low cost and high success rate. Attackers craft messages that impersonate legitimate organizations or contacts, urging recipients to click links, download attachments, or enter login credentials. Spear phishing targets individuals with customized content, increasing the likelihood of deception. Social engineering extends these tactics by manipulating human psychology (typically curiosity, urgency, greed, or authority) to bypass security.

Common attack vectors:

- Generic phishing emails with malicious links or attachments

- Spear phishing with personalized messages targeting specific individuals

- Business email compromise (BEC) impersonating executives or vendors

- Vishing (voice phishing) to extract sensitive info via phone calls

- Smishing (SMS phishing) with malicious links or fake alerts

- Pretexting to obtain information by pretending to need it for a legitimate purpose

- Fake tech support scams asking users to install remote access tools

- Social media impersonation to trick contacts or gather intel

Compromised or Weak Credentials

Compromised credentials are one of the most direct attack vectors. Attackers acquire them through phishing, data breaches, keylogging, or dark web markets. Weak credentials like simple or predictable passwords can be cracked with brute force or dictionary attacks. Credential-based attacks are especially dangerous because they often bypass traditional security measures.

Common attack vectors:

- Use of default usernames and passwords left unchanged

- Password reuse across multiple services

- Brute-force attacks guessing weak or common passwords

- Credential stuffing using breached login data from other sites

- Phishing attacks capturing user credentials

- Keyloggers recording passwords as they’re typed

- Exploited password reset mechanisms lacking verification

- Insecure password storage on client-side or in apps

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks

DDoS attacks overwhelm target systems or networks with traffic, rendering services unavailable. They can be volumetric (flooding with bandwidth), protocol-based (exploiting server resources), or application-layer (targeting specific functions like login forms). The source is usually a botnet, a network of compromised devices controlled by the attacker.

Common attack vectors:

- Botnets launching large-scale traffic floods

- DNS amplification using open DNS resolvers

- SYN flood attacks exhausting server connection queues

- HTTP floods targeting specific application endpoints

- UDP floods exploiting connectionless protocols

- NTP amplification leveraging time synchronization servers

- Slowloris attacks keeping many connections open to exhaust resources

- IoT devices hijacked to generate coordinated attacks

Brute Forcing and Session Hijacking

Brute force attacks use automation to guess passwords, often targeting login interfaces or encrypted files. More advanced versions, like credential stuffing, exploit leaked credentials from previous breaches. Success depends on weak password policies and lack of rate-limiting or lockout mechanisms. Session hijacking occurs when an attacker intercepts or steals a valid session token, allowing them to impersonate a user without needing a password.

Common attack vectors:

- Automated password guessing on login portals

- Dictionary attacks cycling through known password lists

- Credential stuffing using data from previous breaches

- Session token theft via insecure cookies or storage

- Man-in-the-middle interception of session IDs

- Exploiting predictable session token generation

- Session fixation attacks with pre-set tokens

- Browser exploits to capture active session credentials

SQL Injections and Cross-Site Scripting

SQL injection (SQLi) is a code injection technique that exploits input fields not properly sanitized. Attackers insert malicious SQL statements into query fields, allowing them to access or modify the backend database. SQLi can expose sensitive data, alter records, or even gain administrative control over the system. Cross-site scripting (XSS) involves injecting malicious scripts into web pages that are then executed by other users’ browsers. XSS can steal session cookies, redirect users to malicious sites, or alter page content.

Common attack vectors:

- SQL code injected via login or search fields

- URL parameters containing unsanitized SQL queries

- POST request payloads manipulating backend queries

- Stored XSS where scripts are saved on the server

- Reflected XSS from query strings or form inputs

- DOM-based XSS via client-side script manipulation

- Injections in admin panels or CMS backends

- JavaScript-based redirection or data theft via XSS

Best Practices for Minimizing Attack Vectors

1. Continuous Patch Management

Timely updates are one of the most effective defenses against exploitation. Most attackers prioritize known vulnerabilities that have existing patches, as these are easiest to automate and exploit at scale. When patches are delayed, the window of exposure remains open, giving attackers time to compromise systems.

A structured patch management process includes asset inventory (knowing what needs to be patched), vulnerability scanning, patch prioritization based on severity and exploitability, and verification of successful deployment. It’s also important to track failed updates and test patches in controlled environments to avoid compatibility issues. Organizations should monitor vendor advisories and subscribe to security bulletins to stay informed about critical vulnerabilities. Consistency across environments—development, testing, and production—is key to maintaining integrity.

2. Employee Cybersecurity Awareness Programs

Security tools can’t prevent what employees allow in. Awareness training transforms users from potential liabilities into a line of defense. Since attackers often rely on social engineering, teaching employees to spot and report suspicious activity is crucial.

A strong program includes onboarding training, periodic refreshers, role-specific content (e.g., for finance or IT teams), and real-world examples of attacks. Simulated phishing campaigns help measure awareness and reinforce good behavior. The program should also cover safe data handling, device security, physical security (e.g., preventing tailgating), and incident reporting procedures. Integrating security into everyday workflows helps reinforce it as a shared responsibility.

3. Robust Identity and Access Management

IAM systems ensure that the right individuals access the right resources at the right times for the right reasons. When implemented poorly, they can be exploited for privilege escalation, lateral movement, or unauthorized access to sensitive data.

Modern IAM includes identity federation, single sign-on (SSO), MFA, and dynamic access policies based on context (location, device, behavior). Privileged access management (PAM) restricts administrative capabilities and requires approvals or time-based access for critical systems. Periodic access reviews and entitlement management help ensure permissions align with current roles. Strong IAM policies also cover service accounts and machine identities, which can be overlooked but are often exploited.

4. Proactive Threat Intelligence Integration

Threat intelligence turns unknown threats into known ones. By understanding what adversaries are doing globally, organizations can better anticipate and prevent attacks locally. Intelligence sources include threat feeds, honeypots, dark web monitoring, and information sharing groups like ISACs.

Operationalizing intelligence means integrating it into SIEM systems, firewalls, endpoint protection tools, and email gateways. Indicators of compromise (IOCs), tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), and threat actor profiles should inform rules and playbooks. Analysts must assess intelligence relevance and act on high-confidence data to avoid noise. A mature threat intelligence capability enables not just reaction, but threat hunting, red team exercises, and strategic decision-making.

5. Network Segmentation and Micro-Perimeters

When attackers breach a perimeter, unrestricted access to internal systems allows them to cause maximum damage. Segmentation constrains this freedom by placing barriers around critical assets and defining strict communication pathways.

Segmentation strategies include VLANs, subnetting, firewalls between zones, and microsegmentation using software-defined tools. For example, databases may only be accessible to application servers, not directly to user devices. Access controls are enforced at switches, routers, and host-based firewalls. Micro-perimeters go further by enforcing policies at the workload level, often using zero trust principles where trust is never implicit and always verified. Visibility into east-west traffic is crucial for enforcing policies and detecting anomalies.

6. Utilize Penetration Testing

Penetration tests simulate the tools and methods used by real attackers to identify and exploit weaknesses. Unlike vulnerability scans, which look for known issues, pen tests explore unknowns and validate exploitability.

Pen testing can target specific components (web apps, wireless networks, cloud infrastructure) or simulate end-to-end attack paths. Types include black-box (no knowledge), white-box (full knowledge), and gray-box (partial knowledge) tests. A well-scoped test includes clear objectives, rules of engagement, and a remediation plan. Reports should detail findings, exploit paths, potential impact, and prioritized recommendations. Ongoing testing—especially after major changes—ensures defenses evolve with the threat landscape. Combined with red teaming, it can assess both technical and organizational resilience.

Identifying and Mitigating Attack Vectors with CyCognito

Most organizations already know what common attack vectors look like. The real failure is not awareness, it is visibility and prioritization. Teams do not have a complete, current view of what they are exposing externally, how those exposures connect, or which ones materially increase the likelihood of compromise.

CyCognito external exposure management platform addresses this gap by continuously discovering and mapping an organization’s external attack surface from the attacker’s perspective. This includes internet-exposed assets such as domains, cloud infrastructure, applications, APIs, certificates, and third-party dependencies that often introduce high-risk attack vectors without security teams realizing it.

Instead of treating vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and exposures as isolated findings, CyCognito correlates them into exploitable attack paths. This shows how individual weaknesses combine to form realistic routes an attacker could use to gain access, escalate privileges, or move laterally. In practice, this helps security teams focus on the attack vectors that actually matter, not the ones that merely exist.

CyCognito supports attack vector reduction in several concrete ways:

- Continuous external discovery to identify unknown or forgotten assets that expand the attack surface and introduce unmanaged vectors

- Exposure analysis that highlights risky configurations, outdated software, weak authentication, and insecure network access

- Attack path modeling to reveal how multiple low- or medium-risk issues can chain together into a viable breach scenario

- Risk-based prioritization that directs remediation toward exposures most likely to be exploited, rather than those that simply score high in isolation

- Change monitoring to detect when new attack vectors appear due to cloud changes, deployments, or third-party integrations

This approach aligns directly with modern CTEM programs, where the goal is not to eliminate every possible vulnerability, but to continuously reduce the most dangerous paths attackers can realistically use.

By shrinking the external attack surface and breaking high-risk attack paths, CyCognito helps organizations move from reactive exposure management to proactive attack vector control.